“Honoring the legacy of Vladimir Prelog (1906 - 1998) the 1975 Nobel Prize winning organic chemist who pioneered research into the stereochemistry of organic molecules and reactions. ”

Early Life

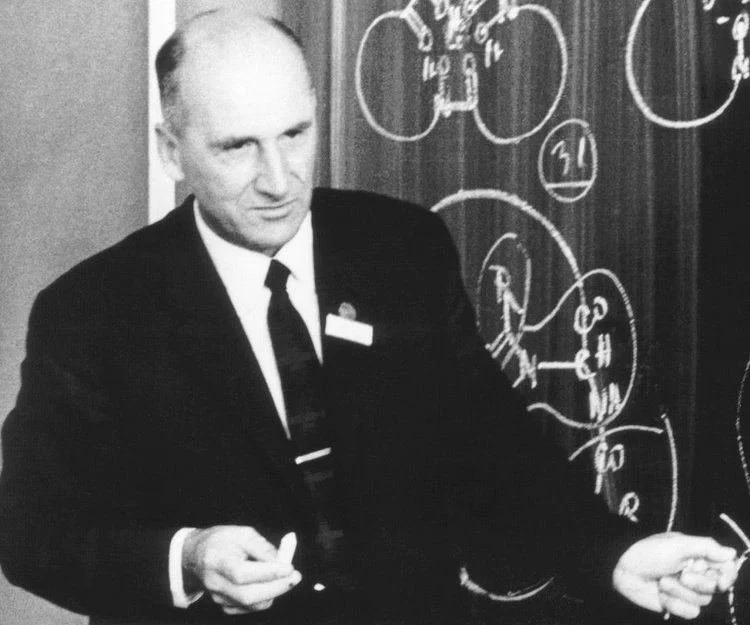

Prelog conducting his first chemical experiments

Vladimir Prelog was born on 23rd July 1906 in Sarajevo. His father Milan and mother Maria moved shortly before he was born to Bosnia and Herzegovina, after his father accepted a job as a high-school teacher (history). His parents did not allow him to play with children of other nationalities, causing him to have a lonely childhood, which he confirmed later. An interesting anecdote of his childhood is that he was present during the visit of Austrian-Hungarian prince Franz Ferdinand. Back then, a large number of children gathered to throw flowers in front of the walking prince. As it happens, shortly before the prince walked by Vladimir, a bullet struck, killing him. That incident, and the consequences of that event, will leave long term trauma on Vladimir, which is why he had an aversion to mass gatherings for the rest of his life, even for good purposes.

He commenced primary school in Sarajevo. At the beginning of the First World War in 1915, after the divorce of his parents, he relocated to Zagreb, where he completed primary school. He lived with his aunt, Olga Prelog, whom he describes as an enlightening and inspiring teacher. Olga greatly stimulates young Vladimir's interest in science, and as a twelve-year-old he conducts his first chemical experiments.

After his father got a new job in Osijek, Vladimir went with him and enrolled in high school in Osijek. There he met his first mentor, chemistry professor Ivan Kurija, who further encouraged Vladimir's talents. There, he becomes a well known name after improving the then widely used automatic titration apparatus, which also resulted in his first publication in the German scientific journal Chemiker Zeitung. The article focused on an analytical instrument used in chemical labs. In his third year, his father got a job in Zagreb, so Vladimir returned with him and completed high school there.

From an ambitious student to respected researcher

In 1924 he relocated to Prague where he enrols into the Czech Technical University, Department of Chemical Engineering. In the beginning, while disappointed in the theoretic and empiric ways of teaching from his professors, Vladimir meets his mentor, and as it happens later his life friend, Rudolf Lukeš. As one of the rare students that was allowed to collaborate with professors at the time, together they research alkaloids as cocaine, quinine and morphine. This collaboration left such an impression on Vladimir, that he would later frequently tell his students : “The best way of studying science is to be an assistant to the master who is an ideal in his field of work and in his personal characteristics”. During one of his experiments with N-methil-2,5-diphenilpyrol, he discovers incredible characteristics of this substance such as triboluminescence. The structure that Vladimir achieved then to this day was not replicated, meaning that this phenomenon is still unexplained. He graduated in 1928 as the highest achieving student in his generation. The pathway to his doctorate was accompanied by numerous difficulties. His father was being retired for political reasons, and Vladimir feared that he would not finish his doctorate before he runs out of money. After accepting the task of researching the recently discovered structure of rhamnoconvolvulin (a form of glucose) for his doctoral thesis, under the guidance of his mentors Emil Votoček and Rudolf Lukeš, he completed the in record time and received his doctorate in 1929.

Prof. Emil Votoček’s lab research lab where Prelog undertook his Ph.D

Life on the move

In the period prior to the biggest economical crisis of all time, Vladimir had difficulties finding a job. Salvation came in the form of Gothard J Driz., a friend of Prof. Lukeš. Wanting to establish a laboratory for the synthesis of rare substances, he employs Vladimir to design it. Since Vladimir could not be formally employed as he was a foreigner, his salary was officially presented as a “assistance from a friend”. Carefully working with Vladimir, Driz becomes informally Vladimir’s first Ph.D. student, even though officially Driz’s mentor was Prof. Votochek. In 1932 Vladimir was called to serve his military term in the then Kingdom of Yugoslavia navy. A year after that he married Camilla Vitek, with whom he will later in 1949. have his only son Jan.

Vladimir and his wife Kamila

Even though he had a large amount of work, Vladimir found time to conduct various experiments. However, that was not enough for him, because he longed for a real academic life. For those reasons, Vladimir moves in 1935. to Zagreb, where he receives as role as assistant professor at the Technical faculty of the University of Zagreb. Even though he finally got the academic life he wanted so much, Vladimir arrived in an empty laboratory with very scarce equipment. He establishes a collaboration with a small local company Kaštel, in a way that they secured financial funding and equipment which he needed, and in return he conducted experiments and research on substances that they wanted. This collaboration very much benefited the small company, which today carries the name of the largest pharmaceutical company in the former Yugoslavia, Pliva. With extensive research, he developed an antimicrobial sulphonamide drug called 'Streptazol', which soon became well-known in the pharmaceutical industry. Even though very successful, that collaboration did not last long because four years later WW2 disrupted life.

Believing that the threat to his life came not from the Nazis, but from some of his compatriots who identified themselves as Ustashas, he accepted the invitation of the president of the German Association of Chemists, Robert Kuhn, to come to a few conferences in Germany. Under the pretext of giving lectures, he left for Germany, but still found a safe haven in Zurich, where his friend and another of his many mentors, Leopold Ružička, lived. After a hard fight over paperwork, Vladimir and his wife officially relocated to Zurich, which will remain his home for the rest of his life.

Not your average professor

Vladimir Prelog giving a lecture

After the flight of many jewish professors from Zurich, Vladimir uses his chance and attain a job in ETH Zurich. He advances quickly, becoming a full professor in 1950. His work with strychnines became famous throughout the world, and soon he comes into contact with famous chemists, sir Robert Robinson and Robert Burns Woodward, who will leave a large impression on his life, and which he called his “imaginary teachers”. He also comes into contact with stereochemistry for the first time, the field that will later help him win a Nobel Prize.

At the time at ETH there was a “monarchy” like structure, where one lead professor led all research projects. When Vladimir arrived in Zurich, Ruzicka was the lead professor, but after his retirement in 1957, Vladimir was elected to that position. Seeing that organic chemistry requires a better research complex hierarchy, in 1965 he makes a “mini-revolution” and introduces a rotary presidency of the complex, led by several important professors, and after that he leaves his position. He was one of the very rare people who voluntarily left that type of position, his main reason being that he thought that the university politics took too much time from his research projects.

The road to the Nobel prize

Prelog receiving the Nobel Prize

The next period of Vladimir’s life was filled with a variety of scientific successes, from Adamantane ((CH)4(CH2)6) to rifamycin and boromycin the bacteriocidal antibiotic. Through his research he becomes a pioneer of stereochemistry. He formulated the Kan-Ingold-Prelog priority rules, which are used in organic chemistry to give names to molecule stereoisomers. His work contributed to understanding the nature of enzyme reactions. His obsession with this field went so far that at one moment he employed swiss artist Hans Erni to paint the molecule formations.

In Zürich, he worked on removing certain compounds called the 'chiral enantiomers' from an organic compound called 'Tröger's base' which contains carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen atoms. He did this by using the chromatography technique for separating mixtures proving that the belief about carbon atoms being the only constituents of chiral molecules was inadequate. He stated that even nitrogen atoms could comprise the centre of a chiral (non-superimposable mirror image) compound.

It all culminated in 1975. when he received the Nobel Prize in chemistry, which he shared with John Cornforth for spectacular research in the field of organic reactions in stereochemistry.

Although he had to retire in 1976, he continued to work at the faculty as a research student. Throughout his life, and especially after his retirement, he did not hesitate to share his knowledge with others, as evidenced by the fact that he lectured at 150 different universities, schools and conferences around the world. He donated a rich collection of books and magazines from his personal collection to his former Department of Organic Chemistry at the Technical Faculty in Zagreb.

He also wrote a book, “My 132 Semesters of Chemistry Studies” an autobiography accounting his entire career. He was active in the scientific sphere even in his nineties.

A man for everyone

He was known as a funny man, of a wide cultural spectrum and full of various anecdotes. People described him as a person who is very adaptable: he is cynical with cynics, optimistic with optimists, funny with pranksters and many other traits that adorned him. But in his soul he was a rationalist, and most of all a philanthropist and peacemaker. Numerous religious and other organizations approached him, asking him for help in various matters, but because of his beliefs he refused. However, when an American high school student sent him a question about his religious beliefs, he replied:

“Nobel prize winners are not more competent about God, religion, or life after death, than other people, but some of them, like myself, are agnostics. They just don’t know, and, therefore, they are tolerant of religious people, atheists, and others. What they dislike are militant zealots of any kind. With best wishes. ”

Death, Awards & legacy

Prelog died on January 7, 1998 in Zurich. He was also cremated there. In 2001, the urn was moved to the tomb of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. His name can also be found on a street in Sarajevo, and every year at ETH Zurich, the Prelog Award for Outstanding Achievements in Chemistry is presented. A commemorative stamp with his image was create by BH Post in 2006 and 2012.

Prelog was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1962 for his contribution to the development of modern stereochemistry. To date, he is one of only small number of individual from the former Yugoslavia to achieve this.

In 1991, along with 108 other 'Nobel Prize' winners, he signed the peace appeal to stop the 'Battle of Vukovar', being held in Croatia.

Awards

Centenary Prize (1949)

ForMemRS (1962)

Marcel Benoist Prize (1964) - for his invaluable contribution to organic chemistry. The prize is often known as the "Swiss Nobel Prize", and is awarded to scientists living in Switzerland.

Davy Medal (1967)

Paul Karrer Gold Medal (1974)

Nobel Prize for Chemistry (1975)

Chirality Medal (1992)

In 2008, a memorial to Prelog was unveiled in Prague.

“The road from Sarajevo to Stockholm is a long one and I am fully aware that I have been very lucky to arrive here. The journey could not have been made without the generous help of friends, colleagues, co-workers and also of numerous chemists before me, on whose shoulders we stand””

Contributors to tribute page

Bosnia & Herzegovina Futures Foundation would like to thank the following individuals and organisations for the contributions to this tribute page:

Danijel Despotovic and Dr. Eddie Custovic

Vladimir Prelog – Facts. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2022. Sat. 22 Jan 2022. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1975/prelog/facts/>

Arigoni, D.; Dunitz, J. D.; Eschenmoser, A. (2000). "Vladimir Prelog. 23 July 1906 – 7 January 1998: Elected For.Mem.R.S. 1962". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 46: 443. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1999.0095.

Vladimir Prelog (1975) Autobiography, the Nobel Committee.

James, Laylin K. (2006). Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 1901–1992. American Chemical Society & Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN 0-8412-2459-5.

Dunitz, J. D. (1998). "Obituary: Vladimir Prelog (1906–98)". Nature. 391 (6667): 542. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..542D. doi:10.1038/35279. S2CID 4374006.

Horvatić, Petar: 23. srpnja 1906. rođen Vladimir Prelog – dobitnik Nobelove nagrade. Narod.hr. Accessed 2 October 2018